Imagine a scene out of a sci-fi movie. Strap on a robotic arm, watch while it contorts your hand and fingers at superhuman speeds, and 30 minutes later you emerge with the Beethoven Emperor Concerto fully conquered and ready to slay.

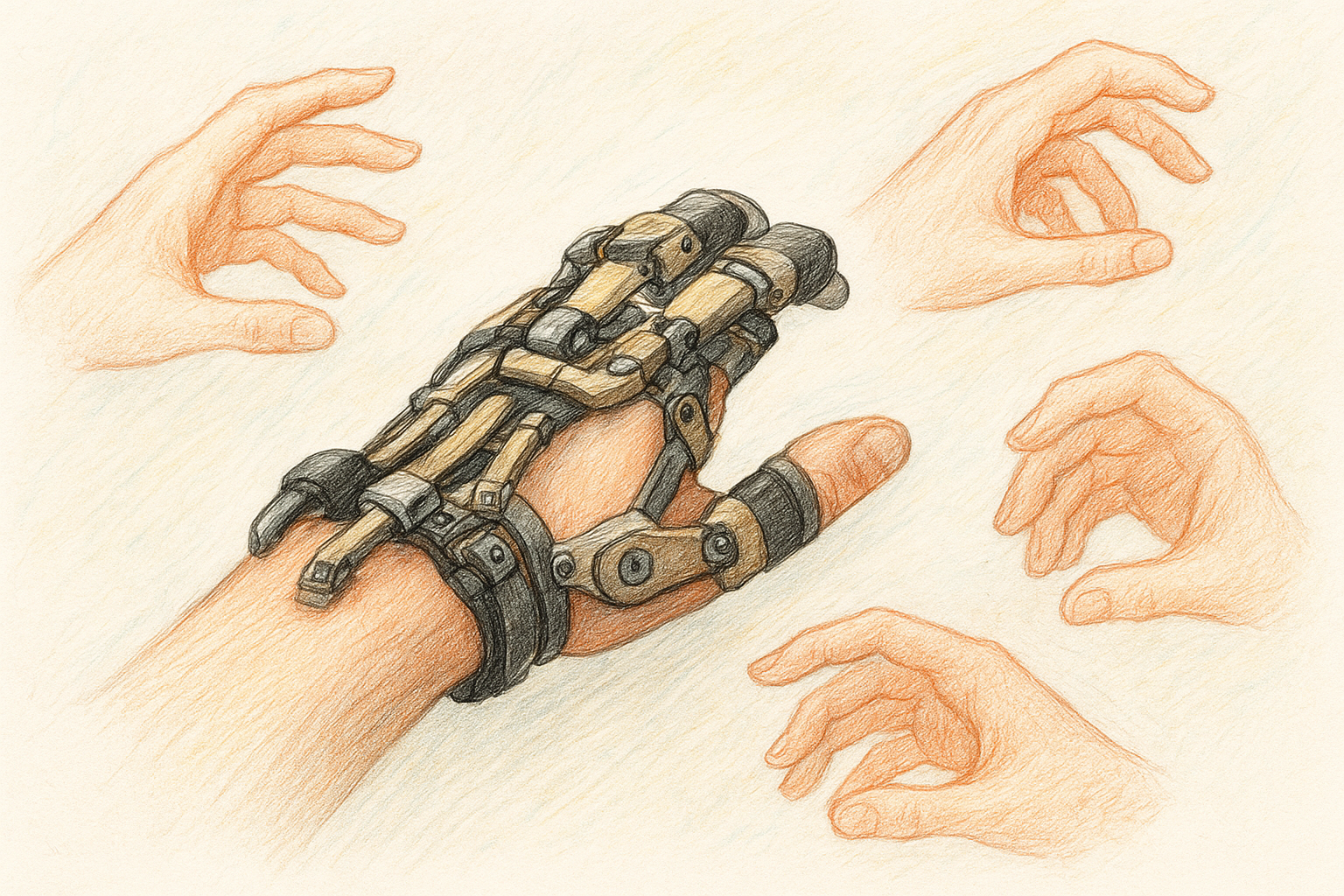

Okay, that is a bit of fantasy. Such a robotic arm does not exist in real life, but this research study by Furuya et al.[1] shows that a hand exoskeleton can teach you how to play faster, and elucidates why the resulting changes to brain programming has real implications for how you should practice.

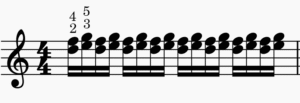

In the paper, the authors built an exoskeleton robot for the hand that can flex and extend each finger independently, and recruited a group of advanced pianists to wear it and let it move their fingers in complex patterns that were beyond what is humanly achievable. The result of receiving this passive training was that the pianists subsequently surpassed the speed plateau which they had hit from just normal practicing. We’ve all experienced the ceiling effect: hitting a plateau after practicing long and hard, without gaining further progress no matter how much harder we try. In the experiments, this ceiling effect was encountered when the researchers asked the pianists to first practice playing a difficult passage at home for 2 weeks, where, upon measuring their keystroke rate, their playing speed was observed to have plateaued within a few days. Then, when the pianists went into the lab to train for 30 minutes with the exoskeleton, their speed increased by 7% immediately afterwards!

What is the neuroscience basis for this incredible finding? By using the technique of transcranial magnetic simulation (TMS) over the motor cortex of the brain, the researchers pinpointed how the somatosensory exposure to novel and superhuman movements, induced by the exoskeleton, lead to altered neural patterns in the brain and reorganized muscular coordination as a result of the exoskeleton training.

This research clearly shows that new sensory exposure, not just more repetitions, is essential for motor skill mastery: through the process of neuroplasticity, practicing with new and different experiences physically changes our brains’ motor programming and reshapes neuronal connections in the motor cortex. When the pianist does not have prior physical experience with the movements required of the complex skill, is when the ceiling is hit and progress plateaus. Feeling the stimulus from novel movements feeds your brain new information that it uses to reorganize your brain circuits and break through a learning plateau.

Long‑term progress comes from changing brain circuits, not just clocking hours.

No Exoskeleton? No Problem!

Most of us will never strap on an exoskeleton. So how should we practice without one? The idea of exposing your hands and brain to new and different movement patterns has deep support in the motor learning literature, and echoes established practices in variability training[2] and reinforcement learning[3].

Previously, I wrote a blog post, Variations on a Scale, on exactly this topic. In variability training, you would practice the skill or passage by playing different variants of it. A common example is to play a scale passage with a dotted rhythm variant, but there are many other ways to devise variants that work well depending on the nature of the passage. In reinforcement learning, the exploration/exploitation dichotomy proposes balancing when to explore new movement patterns to find new and potentially more effective ones, and when to exploit familiar movement habits to further refine them. In technical parlance, this is the process of escaping from a local optimum—a low hill, for example, where your existing habits have hit a ceiling on how well they work—to finding a global optimum—that is, reaching for the tallest mountain, but where, in order to start ascending the highest peak, you must first navigate your way through a valley of new and unfamiliar movements.

You can read my blog post here for some concrete examples of how to implement variability training and reinforcement learning in your piano practicing. In light of the research findings in this paper, I’ll add a few more ideas that make for worthy replacements for an exoskeleton.

(I) Over-tempo

In direct contrast to the popular “slow practice” approach, practicing over-tempo is about practicing (certain) things faster than you normally would play it.

- An Example: if you have a big leap in your piece, practice moving from the note before the leap to the note after the leap in less time than you would have when playing the piece at the usual tempo, but without sacrificing accuracy.

- The Parallel: mimics what the exoskeleton did by moving the pianists’ fingers faster than they could on their own.

- The Methodology: break down passages into miniature chunks to take over-tempo, without sacrificing accuracy or technique. Remember, this is not for performing fast, but rather for feeding your brain novel movement experiences.

- Good For: leaps, octave passages, block chords, and anywhere that efficient movement is paramount.

(II) Slo-mo with exaggeration

This is slow practice with a real neuroscience purpose.

- An Example: a good way to slow practice a fast scale passage is the “soldier march”: exaggerating the fingers’ motions on each keystroke, as if they were doing a high march like a soldier.

- The Parallel: instead of relying on a machine to supply new somatosensory input, you are amplifying your own subtle movements to augment the information that your own body provides to your brain. This breaks down complex movements into observable and memorable experiences, and also taps into the exploration half of the exploration/exploitation dichotomy.

- The Methodology: Play each note one at a time, at a slow and comfortable pace, and exaggerate how you would move your finger, hand arm and body when going from one note to the next. Ways of exaggeration include making the movements bigger, or making the transition between notes swifter. You can also exaggerate voicing and dynamics. Carefully attend to the feel and effect of the movement. (If you’re concerned that it looks stupid, don’t worry, “practice like no one is watching.”)

- Good For: scale passages, two-hand coordination, anywhere that precision and suppleness intermingle.

(III) Bilateral, cross-education exercises

Learning a skill in one hand can benefit the other hand.

- An Example: when learning a new technique, say, tremolos, have both hands learn the same tremolo passage, even if it appears for only one hand in the piece. Even better, have both hands play the tremolo in mirror-imaged configuration.

- The Parallel: a fascinating finding in the paper was that training one hand caused the other hand to improve. This is due to cross-talk between the two hemispheres in our brain[4, 5], so that developing one side of the motor cortex by training one hand can have benefits for the other hand as a result.

- The Methodology: tricky passages for one hand can be learnt in both hands, and played hands together or hands separately. You can also use the symmetric transfer technique of mirror-imaging the two hands so that the kinesthetic feeling of the movements in the stronger hand can be transferred to the weaker hand.

- Good For: equalizing the skill disparity between hands, transferring skills from the stronger hand to the other.

See my blog post and video for more on symmetric learning for cross-education!

Conclusion

A robot has a lot to teach us about movement and technique. It highlights that brain development and neuroplasticity is the basis of motor skill mastery. And even when deliberate practice hits a technical ceiling, this exoskeleton research points to innovative ways of continuing to bolster our neuroplasticity for learning.

My last word on this, however, is that despite the incredible insights this exoskeleton research study gives on developing motor skills, playing the piano is not just about playing faster, but playing with musicality and intention. That is something no robot can teach.

References

- Shinichi Furuya et al., Surmounting the ceiling effect of motor expertise by novel sensory experience with a hand exoskeleton. Sci. Robot.10, eadn3802 (2025). DOI:10.1126/scirobotics.adn3802

- Wulf, G., & Schmidt, R. A. (1997). Variability of practice and implicit motor learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 23, 987–1006

- Dhawale AK, Smith MA, Ölveczky BP. The role of variability in motor learning. Annu Rev Neurosci 40: 479–498, 2017. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-072116-031548

- Rodrigues AC, Loureiro MA, Caramelli P. Musical training, neuroplasticity and cognition. Dement Neuropsychol. 2010 Oct-Dec;4(4):277-286. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642010DN40400005. PMID: 29213699; PMCID: PMC5619060

- Houdayer E, Cursi M, Nuara A, Zanini S, Gatti R, Comi G, et al. (2016) Cortical Motor Circuits after Piano Training in Adulthood: Neurophysiologic Evidence. PLoS ONE 11(6): e0157526. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157526

Leave a Reply