One Hand Washes the Other (Idiom) — Two parties share their unique strengths, each benefitting through mutual exchange.”

It comes as no surprise that as pianists, most of us have a dominant hand and a weaker hand. What I find more interesting is that each hand has developed its own unique skill sets and strengths as a result of playing classical music with stereotypical patterns for each hand—the right hand carrying the melodies and intricate passage work, and the left hand containing accompaniment figurations that can themselves be complex and demanding.

As learners, we can use our individual hand’s unique skills to our advantage: we can transfer skills from our stronger hand to our weaker hand. Sometimes when I encounter a challenging passage in one hand, I may find that the same technique comes naturally to the other hand, and amazingly, playing the same passage with both hands together makes the difficulties melt away! It is as if my stronger hand is guiding my weaker hand to play with the correct movements.

Symmetric, or mirrored, self-learning facilitates motor skill acquisition through mimicking one’s own hand.

Learning through mimicking one’s own hand is a fantastic way to learn the motor skills involved in a given technique. The kinesthetic feeling of the movement is already internalized in one hand, and is readily available for transferring to the other. Playing mirror-imaged engages both hands to move with identical motions, and playing hands together gives immediate feedback to make corrections and adjustments in real time. This approach of symmetrical, or mirrored, self-learning is more efficient than learning it from scratch or from an external source.

Symmetric learning is a fascinating area of neuroscience that studies how humans learn through mirror effects and motor mimicry. When I discovered how to apply it to piano playing in the form of self-learning, I was amazed at how quickly it enabled me to grasp new skills and refine existing movement habits. Now whenever I see the opportunity to “transfer skills” between hands, the very first thing I do is to invent an exercise for mutual learning between my hands.

Tips For Symmetric Self-Learning

After systematically applying symmetric self-learning to my own practice, here are some tips and principles that I have observed worked best.

- Play hands together, trying to match the motions of the stronger hand. For example, are the wrists at the same level? Are the hand positions the same and do the fingers striking the keys identically? The primary goal of this learning exercise is to make both hands’ motions identical, whereas producing the same sound is a by-product of achieving the goal.

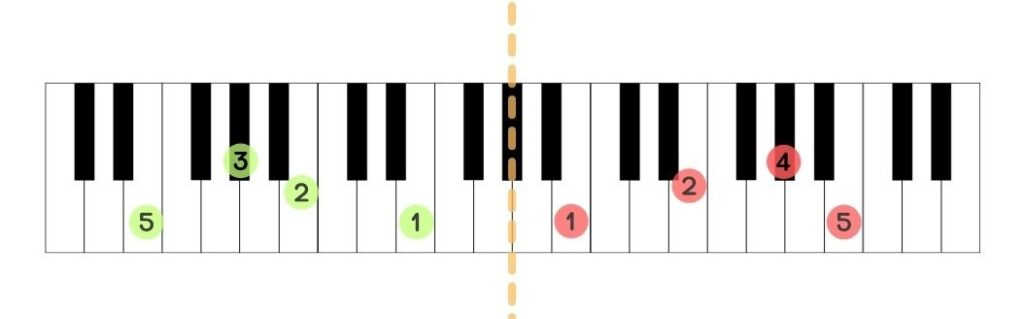

- Devise exercises with symmetric hand positions. This necessarily implies playing in contrary motion. Similar motion and non-symmetric movements do not achieve the crux of this learning tool, even if they may be helpful for other situations.

- Due to the keyboard topology, each hand may need to play different notes/chords in order for them to be in a truly symmetrical position. (More explanation in the case study below.)

- Focus on the kinesthetic feeling of the motions. It would feel natural for the stronger hand and initially novel for the weaker hand, but as the weaker hand adjusts to the new motions, it should start internalize the motions into its movement vocabulary.

Case Study – Arpeggios

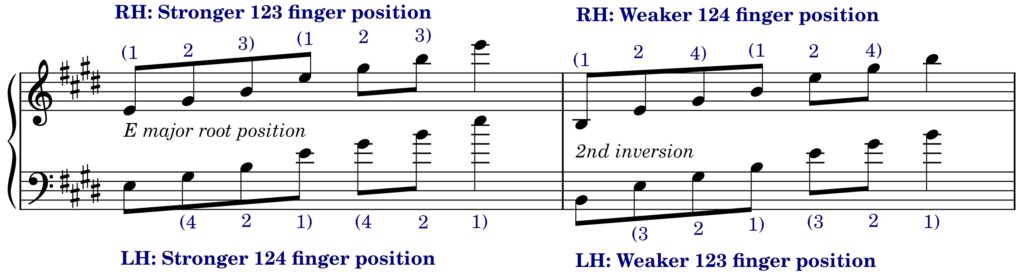

Arpeggios are a fascinating case study for self-learning. Copious amounts of rote practicing of scales and arpeggios marked my musical upbringing. Always starting with ascending from the tonic, it is no wonder my hands are stronger at the fingering and hand positions associated with root position arpeggios. In the example of the E major arpeggio, the right hand is stronger at the 123 fingering, whereas the left hand is better trained at the 124 fingering:

This chart also reveals each individual hands’ strong and weak suits, and presents a perfect opportunity for each hand to transfer its respective strengths to the other!

Learning the RH’s 124 finger position from the LH.

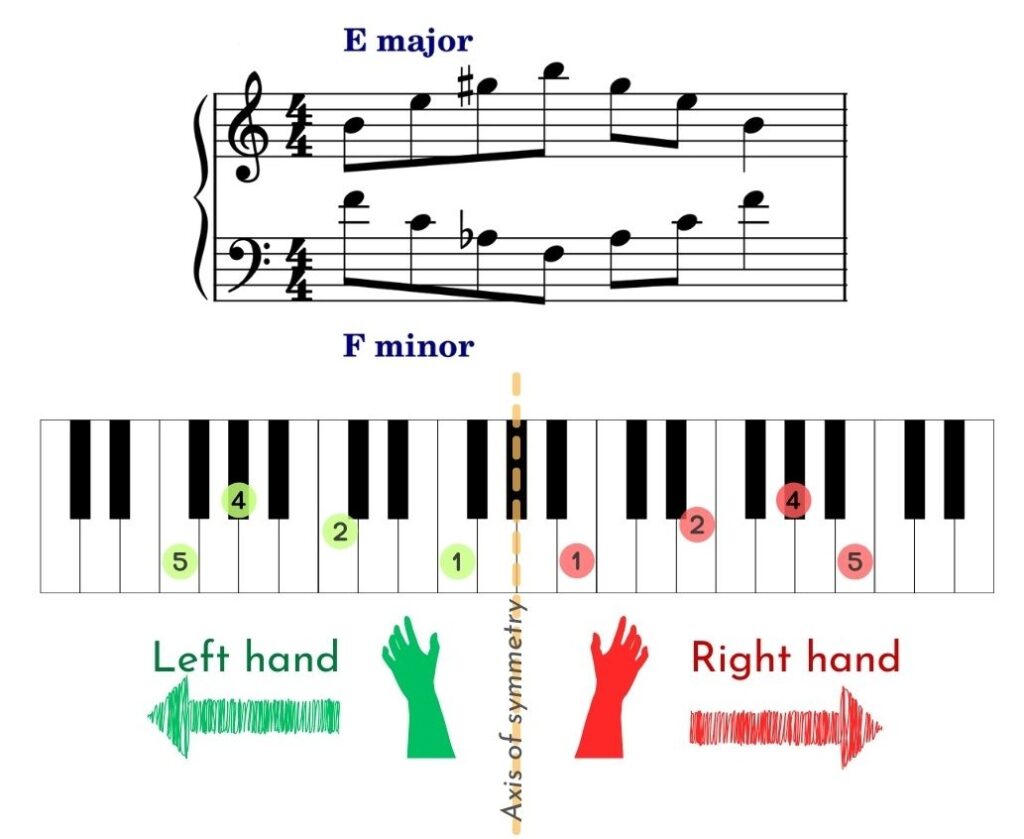

The initial setup for symmetric self-learning requires some careful attention. For tip #3, to create truly symmetrical motions on both hands, the two hands should NOT both be playing in E major. Instead, let’s analyze the keyboard topology and identify two axes of reflection around which the keys are symmetrical: one through the G#’s and one through the D’s. Reflecting the E major chord in the RH around the G# axis places the LH in F minor. This ensures that the spacing between fingers 1, 2 and 4 are identical for both hands, and moreover, the topology of the surrounding black keys are also identical1. There is no other configuration that produces an exact mirror image of E major. I challenge you to try!

This nice mathematical analysis, unfortunately, ends up with a cacophonic clash of E major with F minor—not very pleasant for our tonally-inclined ears2 and somewhat mind-bending to play. I assure you, however, that the motor skill learning benefits are enormous.

Once I’d identified the relevant arpeggios to play, playing the exercise immediately revealed a long-time deficiency with my right hand’s technique: by feeling the subtle difference in how my both hands moved, I realized that my right index finger did not pivot quite as much as my left’s on the descending arpeggio, which was what hindered the thumb-to-4th finger cross over. Wow, it took me under a minute to uncover and fix this decades old bad habit!

If you are wondering why this exercise does not use E major in both hands, it is because the fingering, spacing between fingers, and spatial configuration of the surrounding black keys are all different3. This means that one cannot rely on matching the kinesthetic feeling of the two hands—the key mechanism for skill acquisition in symmetric self-learning.

Conclusion

Symmetric self-learning can be applied to many things: octaves, chords, ornaments, articulation, voicing, and the list goes on. Check out my video for more examples!

While it may seem that hand-to-hand skill transfer is limited to skills you already have, you’d be surprised by how much in sum total the two hands can share with each other, and how much new movement patterns come naturally to one hand that the other can then learn from. I encourage you to incorporate symmetric self-learning into your learning toolbox, and have one hand wash the other to reap the mutual benefits. Don’t let each hand go it alone!

Footnotes

- The surrounding topology is important because nonplaying black keys affect the location on the key and the curvature of the fingers, etc. ↩︎

- You may find various examples of symmetric exercises that range from Debussy-esque to Stravinsky-ian sounding. A neat bit of trivia: The only key whose symmetric counterpart is itself is F# major! ↩︎

- It may be tempting, for arpeggios played on all white keys, such as C major, to break the symmetry by playing both hands in the same key, but the different topology of the surrounding keys may still require a different curvature of the fingers or angling of the hand. ↩︎

Leave a Reply