Few topics in music pedagogy spark as much debate as the value of practicing scales. Many musicians swear by them as the backbone of technique—building common musical patterns that can be applied to any piece. Others dismiss them as tedious or outdated, claiming that learning happens best through repertoire.

I am less interested in taking sides, than in exploring what happens inside the brain when we practice scales or learn repertoire. Neuroscience gives us a fascinating lens through which to view this debate: whether you practice scales or skip them, your brain is ultimately striving towards the same goal—that of building robust neural pathways that you can rely on in performance.

What does it mean to develop neural pathways when learning new skills? I came across a fantastic analogy in the book, Learn Faster, Perform Better, which presented a very vivid and easily understandable analogy for this neuroscience concept.

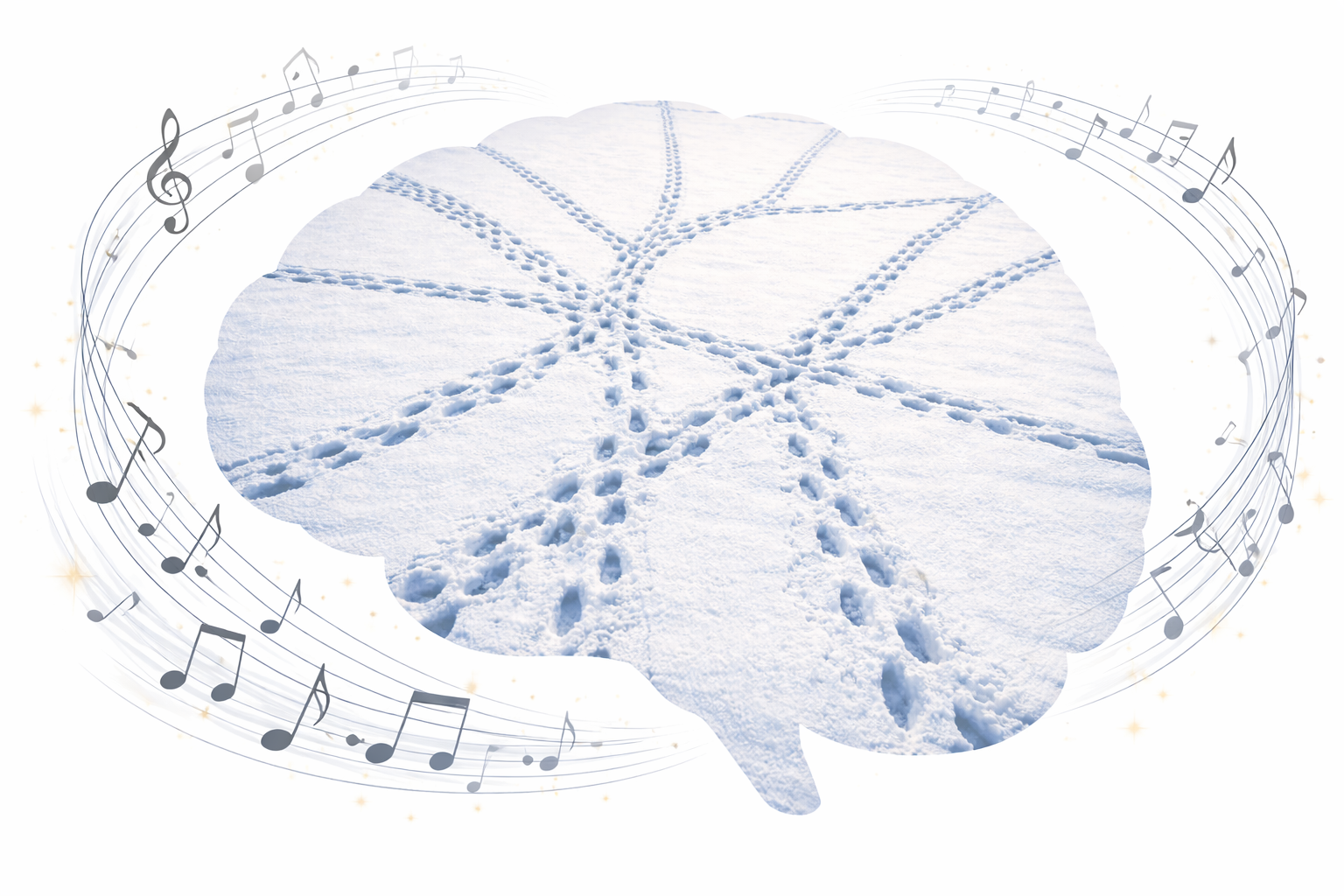

Learning a new skill is like making foot paths in the snow. Imagine you live on one side of a large field covered with a thick layer of fresh snow, and you want to visit your friend on the other side of the field. The first time, you find it difficult to walk through the deep snow, and you may lose your way because it is hard to see where you are going. But after visiting your friend a few times, you find the best route, and your footprints have made a walkable path. It’s now much easier to go visit your friend!

– Adapted with permission from Learn Faster, Perform Better

Trampling along the foot path is analogous to building neural pathways when practicing a skill repeatedly. You develop a channel to fast-track the execution of the skill, allowing electrical signals that control your muscle movements to travel quickly along the reinforced neural pathways.

A Tale of Two Universes

Casting the scales debate in this light, I’ll expand on this “snowy field” analogy to illustrate what happens when you practice scales, or not. Imagine two parallel universes: the senza-scales (without scales) universe, where you learn through playing repertoire only; and the con-scales (with scales) universe, where scales and foundational exercises form a core part of your practice regimen.

Scene 1 (Shared Learning):

You and your neighbors go visit friends.

Senza-scales (without scales) universe. As you make your way across the snowy field, you notice that your neighbors are also visiting their friends across the field. Each of you has trampled your own paths, criss-crossing through the field, and sometimes overlapping at segments to take advantage of the paths that other neighbors had previously made. Though ad hoc, the rich network of paths provides efficient and flexible tracks for everyone.

Neuroscience Analogy: Visiting your various friends represents “learning new pieces”, and the creation of overlapped paths is analogous to your brain consolidating information—linking and reinforcing common patterns for easy reusability.

Con-scales (with scales) universe. Before going to visit your friend, you take out your shovel and start ploughing your path. Why not be helpful to your neighbors, since they want to visit their friends across the field too? So you identify some common paths they might take, and start plowing those too. After you’re done, you’re ready to go visit your friend. Fortunately, most of your path coincides with one of the paths you’d plowed, and it is mostly an easy walk! Your neighbors also thank you for making their commute easier.

Neuroscience Analogy: Plowing the common paths represents “practicing scales,” and your brain has strengthened the neural pathways for the movement patterns found in scales.

Scene 2 (Adaptibility):

Your friend has moved one street down.

Senza-scales universe. No worries, it’s still close by! You just have to make a small change in direction at the end. That means forging a new path, but it’s only a small deviation away from your previous path. Adapting to small changes is easy.

Neuroscience Analogy: Because you have built your paths through varied experiences, your brain has developed flexible neural connections, making it easier to adjust to small changes and build upon the existing network of connections.

Con-scales universe. Unfortunately, because you had plowed the paths so well, the snow banks are so steep that it is difficult to step off the plowed path. Even though it is a small deviation, you find it hard to climb over the banks, and it takes you considerable effort to make even that small deviation.

Neuroscience Analogy: Overtrained skills and deeply ingrained habits are hard to change.

Scene 3 (Individualism over Integration):

A few of your neighbors don’t get along well.

Senza-scales universe. The hostile neighbors trample their own path across the field. They make the shortest path to their destination, ignoring the paths that had already been made by their friendly neighbors. Each direct path they make is more effortful than taking advantage of existing paths, but they don’t care. No one else can use their path. Worse, they sometimes mess up existing paths!

Neuroscience Analogy: Learning pieces without recognizing the connections between them is inefficient and potentially harmful.

Con-scales universe. Even though the hostile neighbors do not care for the kindness of their neighbors, the cleanly plowed paths are just too convenient to ignore. They use the paths, though without any gratitude to the person who plowed it.

Neuroscience Analogy: Trained skills are still available to you even if you aren’t consciously trying to use them.

Conclusion

In the end, our practice habits—whether built on scales or on repertoire—are simply different paths across the same snowy field. What matters is awareness: knowing how neural pathways are being reinforced, and how to keep them adaptable.

Whichever side you sit on, it is important to mitigate the downsides of that approach. If you are in the pro-scales camp, try practicing scales with variations and expanding to a broader variety of foundational exercises, to avoid overtraining a single movement pattern. If you prefer to learn through repertoire alone, pay extra attention to drawing connections between pieces, to ensure you consolidate the skills learnt across pieces—this facilitates implicit motor chunking and pattern abstraction.

Neuroscience also offers more insight and nuance than what the above analogies can encapsulate: that the brain consolidates and prunes these neural pathways during sleep and rest; that playing pieces in a musical context engages distributed pathways involving motor, auditory and visual circuits; that fluency in basic skills serves as a foundation for hierarchical orchestration of motor chunks; that repertoire practice can mimic contextual interference (aka interleaved practicing) and outperform blocked drills.

When done in the right way, either approach can create a rich landscape of movement and memory that lets your skills transfer naturally between pieces. The real art of practicing lies not in choosing sides, but in knowing how to sculpt adaptable pathways through the snow.

Leave a Reply