Since starting this blog, I have been meticulous about avoiding any language containing negative instructions and internal focuses of attention. How hypocritical would it be for me to say, “don’t use negative instructions!”

We are all too familiar with negativity. Don’t rush! Don’t raise your wrist! Don’t be stiff! Not too loud! But not too soft! Who hasn’t heard these refrains from a teacher (or taught these to their students)? Conventional wisdom and popular culture have convinced most people of the undesirability of negative instructions. Yet, we still use them all too often!

Positive vs Negative Framing

Negative framing is detrimental to the learning process in many ways. Mentally, it ironically puts the incorrect action at the forefront of the learner’s attention. Psychologically, it causes a mental block and is a factor in chocking under pressure [Oudejans et al. (2013)]. At a practical level, negativity provides the learner little guidance on what the correct action should be.

When a mistake is identified, a knee-jerk reaction is to simply say, “don’t make that mistake!” Or a more cajoling version, “try not to make that mistake!” The inquisitive learner will remark that negatively framed instructions are vague, subjective, and lacking in specificity about what the correct action should be. The resourceful learner will further proceed to seek out the actionable corrections to make (with bonus points if they are external focuses!), in an effort to convert negative framing to positive actions.

The aspect of negativity I address in this post is this lack of specificity on what to correct or how to improve. If positivity is the negation of negativity, then positively framed instructions are precise, actionable and motivating. (Here, motivating is used in the OPTIMAL Theory sense: autonomy and enhanced expectancies. See this previous post and the references therein.)

Positivity does not mean praise. Nor does it necessitate encouragement (though an encouraging learning environment is beneficial for other reasons, regardless). Rather, positivity is about being cognizant of how framing and word choices affect the learner’s mindset: frame the task in such a way as to increase her ability to achieve the goals.

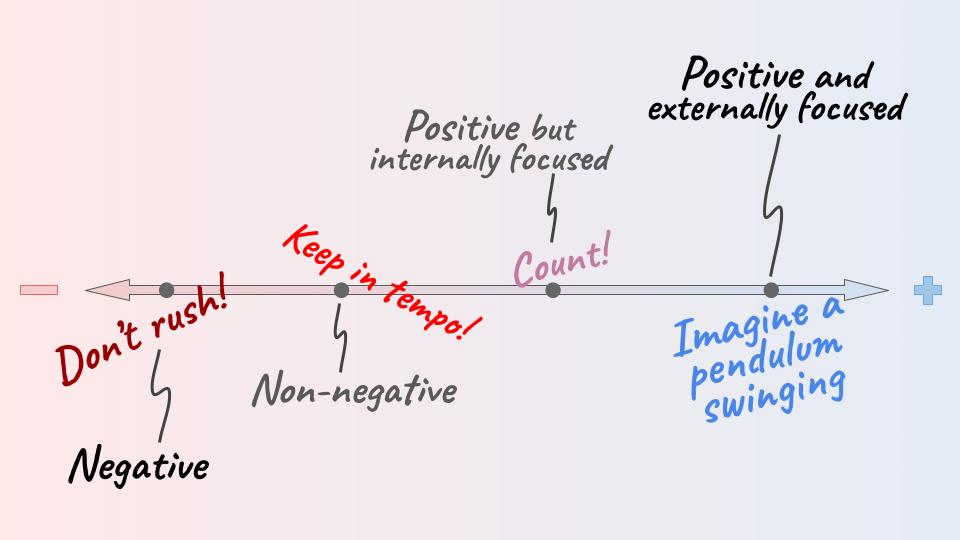

Consider this progression of instruction styles along the spectrum from negative to positive.

- Negative: don’t rush!

- Non-negative: keep in tempo!

- Positive but internally focused: count!

- Positive and externally focused: imagine a pendulum swinging OR sing how the phrase should sound OR pair playing in a teacher-student scenario OR listen to the rhythmic subdivisions of the note being played OR …

We observe that “don’t rush” is not useful: where am I rushing? What does not rushing look like? Why am I rushing? Often, there are also a myriad of underlying factors that caused the error—technique deficiencies, limitations in musicality and audiation skills, lack of awareness, performance anxiety, distractions, personality traits. Negative instructions usually fail to address the root causes.

Non-negative framing may be a step in the right direction, but merely rephrases the same vague instruction without providing actionable corrections for the learner.

With positive framing, there is a whole range of possibilities for corrective action. Which one is appropriate for the situation depends on the root causes for the error, as well as the learner’s individual learning style.

- For a learner weaning off a metronome, imagine a pendulum swinging may help with the transition towards internalizing the tempo.

- If the learner has difficulty understanding what the correct execution of the phrase is, find a way that she intuitively identifies with, to gain that understanding. That may be reproducing the phrase in a different instrument or medium, such as singing (along) or clapping or gesturing (see also the Audiation Practice Tool I reported on in my previous post). Listening back to a recording can also be highly instructive.

- If the learner does understand what the correct phrase should be, but has difficulty producing it, look for technical solutions. For example, intentionally play out-of-tempo but with swift preparation of the hand over each note before playing; then, follow with playing in tempo with the same hand preparation. For another example, in a passage with faster subdivisions of notes being played, listen to the pulse of the faster notes.

- In a teacher-student setting, the teacher can play along with the student to mediate her tempo. This is imitation learning and also excellent immediate feedback for the student.

As we can see, a single type of error may have drastically different actionable corrections depending on the situation!

A note on internal focuses of attention. Although internal focuses are more actionable than negative instructions, we know from motor learning theory that they are still less effective than external focuses. Therefore, aim to design corrective actions that involve responding to the environment or interaction with external objects.

Turning Negative Into Positive

Here are some additional ideas for turning negative instructions to positive external focuses. All examples in I present in this post are adapted from my teachers and from some of my own practicing and experimentation. Use them as ideas for developing your own positive framing to suit your individual learning needs.

| Negative | Positive and Externally Focused |

|---|---|

| Don’t raise your wrist | Press into the keys through your palms (like flattening out play-doh!) |

| Not too loud… but not too soft! | Raise the dynamic to mezzo forte, but keep it less than the forte at the climax |

| Don’t overpower the melody | Play each note separately while listening to the correct dynamic balance, then put everything together again |

| Don’t over-pedal | Listen and clear the sound at changes in harmony |

| Don’t mess up!! | (Direct your attention to your external focus) |

If you are a learner receiving negative instructions, dig deeper: seek out the positive framing that works for you. Finding the appropriate framing is an art, and will become easier with experience and proper guidance. If you are a teacher who tends towards the negative end of the spectrum, I encourage you to incorporate positivity into your teaching philosophy—why leave it up to your students to figure out how to properly reframe your negative instruction?

Coming up with appropriate and effective positively framed instructions takes a lot more effort—it has to be crafted for the specific circumstance of the error, and tailored to the learner’s individual learning style. But the investment pays bigger dividends for learning.

“Narrating the Positive”

When the learner has successfully made the corrections, it is also worthwhile to take a moment to recognize how the specific correction led to a resolution of the original error. This is the flip side of the same coin: not only should errors be positively framed, the corrected outcomes should be, too. To continue with the “don’t rush” example,

- A positively framed observation is, “the passage sounds more crisp rhythmically because I could hear the 1/16th note subdivisions very clearly.”

- A negatively framed observation is, “I didn’t rush this time!”

This is what Doug Lemov refers to in his blog post as “narrating the positive”: when observing a successful outcome, being able to state in an objective and non-judgmental way the specific actions that achieved the outcome.

What are your positive and externally focused instructions? I’d love to hear!

References

Doug Lemov. What Is Positive Framing: An Excerpt from TLAC 3.0 https://teachlikeachampion.org/blog/what-is-positive-framing-an-excerpt-from-tlac-3-0/

Oudejans, R. R. D., Binsch, O., & Bakker, F. C. (2013). Negative instructions and choking under pressure in aiming at a far target. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 44(4), 294–309.

Leave a Reply