In the previous post, we discussed the implications of positive and negative framing for the learning process. In this post, we carry the principle of positivity over to the performance situation. To set the stage (no pun intended), let’s start with a literature review of a research paper on “choking under pressure”, before discussing how positivity ties in with attentional control and goal setting.

Literature Review: Choking Under Pressure

In an extensive study of the factors causing performance failure among pianists, [Furuya, Ishimaru & Nagata (2021)] revealed causal relationships between specific types of “functional abnormalities” induced by performance pressure leading to errors in the performance. Commonly referred to as “choking under pressure”, the authors identified that, for example, passive behaviors such as risk-aversion and delayed reaction to unexpected hiccups may lead to memory slips, poor note accuracy and stunted musical expression.

Another interesting finding is the correlation between functional abnormalities and personality traits of the performer. For example, motor function inhibition (such as tenseness and stiffness), perhaps caused by a feeling of loss of body control or perceptual confusion from an unfamiliar instrument, is amplified under pressure by the performer’s personal tendencies towards neuroticism, anxiety, public self-consciousness, and negative thinking.

The paper’s findings support distraction theory as a plausible explanation for choking under pressure, and also acknowledge the premise of explicit monitoring theory which posits a disruption of automatic skill execution and muscle memory. Each of these competing theories have differing neurological underpinnings, and involve different allocations of resources for attention and working memory during a high pressure situation [Yu (2015)].

While mental health interventions such as re-framing negative thoughts or reappraising a stressful situation are unarguably important measures for combating choking, I’ll focus the rest of this article on attentional control during the performance itself. The ability to control one’s attentional focus during a performance is imperative for tuning out distracting thoughts and task-irrelevant stimuli, and for directing one’s attention towards the performance task.

Attentional Control Through Positivity

For me, practicing concentration—how to control my attentional focus—is an inseparable part of my practice regimen. Just like how, in the art of meditation, quietening one’s mind and focusing on one’s breathing takes daily practice, the analogy to performance is that being able to firmly push away distractions and focus one’s attention on the performance task also takes daily practice. Furthermore, the more that one intentionally practices attentional control, the more readily it is to summon in times of stress. That is to say, attentional control in the practice room transfers to the performance stage.

This is my approach which I recommend for practicing concentration.

- Throughout the preparation process, always learn and practice pieces with deliberate use of focuses of attention. It can be an external focus like “wrist bounce” or “stroke the keys”, or an auditory imagery of your desired voicing or interpretation for the passage. At the minimum, be conscious of your thoughts while practicing, and take note of those focuses that consistently yield the desired outcome.

- If you find yourself distracted while practicing (by work, life, or what’s for dinner), take it as an opportunity to practice controlling your attentional focus. Conversely, if you never ever have any distractions in your life (lucky you), artificially incorporate some distractions on a regular basis. Treat attentional control like meditation: as a daily practice.

- As discussed in the previous post (link), positive framing matters. Utilize positive framing in your focuses. Negative thinking, one of the factors identified in the paper, can amplify choking under pressure.

- Leading up to a performance (any performance, from just a simple run-through in the practice room, to a masterclass or lesson, to a recital) review the focuses that you have found to be effective, making sure that you have your focuses planned for every moment in the piece.

- There is no guarantee that you will not be affected by pressure during the performance, but at least you have a game plan for what to do in the stress of the moment.

Goal Setting

Related to planning one’s attentional focus is goal setting for a performance. It may sound basic, but I learnt these important life lessons of how to set meaningful and achievable goals only as an adult competitive figure skater. A passive “let’s hope for the best” approach lacks purpose and determination, while the Type-A personality’s desire “to win” or “to perform perfectly” each time can backfire to become a mental distraction during the performance. Perfection is a long term (or eternal) goal that spans the entire preparation process, involving careful planning. On the other hand, performance goals are short term goals for playing to the best of one’s ability at that particular performance.

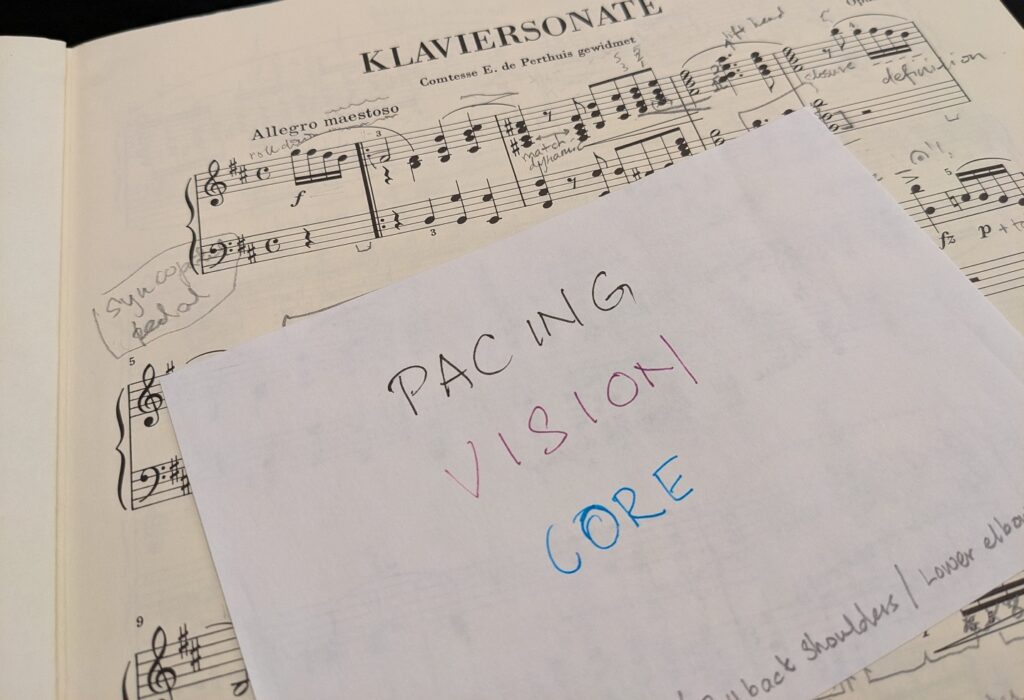

Performance goals should be specific and measurable, and they should be within the performer’s ability and control. If the performance is one step along the journey towards a long term goal, the goals should stretch the performer to improve towards the long term goal. For example, in one performance I gave at an early stage of learning the Chopin Sonata Op. 58, I was not yet note-perfect, my interpretation was still raw, and I also had difficulty with controlling the pacing throughout the piece (which makes it even more susceptible to choking under pressure). Expecting to abolish every flaw for this particular performance would be beyond my then-current ability, so I singled out the one that I deemed most crucial to my long-term progress—pacing—and set myself the goal to achieve that successfully. I didn’t concern myself with playing perfectly, but I aimed for executing a specific task well.

It is worth reminding ourselves that each of our personal progress goes beyond any one performance, and performances are themselves a learning opportunity. It is also important to remember that a single performance failure does not invalidate the entire preparation process. If the preparation is sound, a blip in the works is inconsequential in the long run. A wise piece of advice is, trust in the training.

References

Furuya S, Ishimaru R, Nagata N. (2021). Factors of choking under pressure in musicians. PLoS One. 2021 Jan 6;16(1):e0244082. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244082. PMID: 33406149; PMCID: PMC7787383.

Yu R. (2015). Choking under pressure: the neuropsychological mechanisms of incentive-induced performance decrements. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015 Feb 10;9:19. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00019. PMID: 25713517; PMCID: PMC4322702.

Leave a Reply