External focus, imagery, autonomy, self-efficacy. Now that we’ve covered the major concepts in motor skill learning in my initial blog series, “A First Look at Motor Skills,” it is time to take a more formal look at the literature. We’ll review the OPTIMAL theory of motor learning [Wulf & Lewthwaite (2016)], a unified framework proposed as the culmination of decades of research in motor learning and converging findings of multiple lines of research studies.

What is motor skill?

At it’s most basic, motor skill is the ability to perform movements involving complex muscular coordination. A higher skill level produces better movement outcomes: balance, control, precision, form, speed and endurance. For sports involving equipment, such as basketball, tennis, or rhythmic gymnastics, desirable movement outcomes usually involve equipment-related objectives (e.g. scoring the basketball through the hoop). In music, the aim is to produce beautiful music through refined movement and skillful interaction with an instrument. Additionally, music-related motor skills also includes the proficiency to play scales, arpeggios, and many common note patterns that appear in various guises in the music repertoire, without needing an extended learning period.

Because desirable movement outcomes are measured by the attainment of a ultimate goal, they do not dictate the specific muscular-level action to use, nor the technique, for achieving the goal. For example, in figure skating (my other hobby), the iconic Axel jump can have different techniques for executing the take-off (skid the edge or push straight up off the toepick), even though the desired outcome of the jump is simply to complete the 1 1/2 revolutions in the air. Yet, the quality of the action is what determines the goal’s success. High quality movements leading to successful outcomes is what we recognize as skill mastery.

What does the OPTIMAL theory say about motor learning?

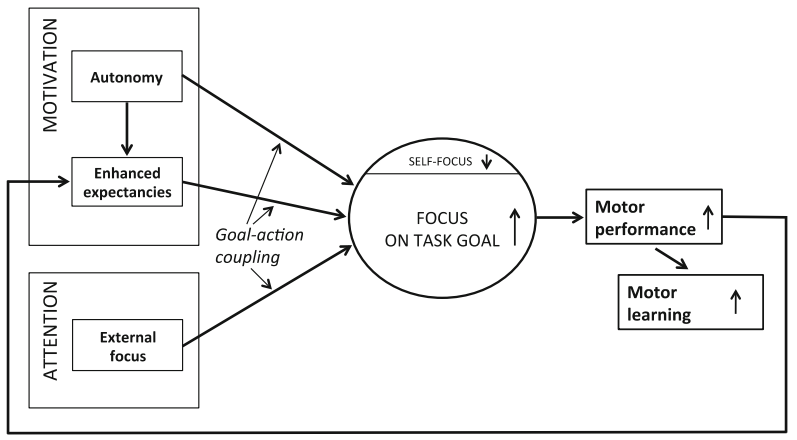

OPTIMAL stands for “Optimizing Performance through Intrinsic Motivation and Attention for

Learning”. At the center of the OPTIMAL theory is the notion of Goal-Action Coupling: a mechanism where a learning environment, enriched with the proper kind of attentional focuses and motivational elements, improves the quality of the movement (i.e. the action) by 1) increasing the focus on the task (i.e. the goal), and 2) diverting consciousness away from the self. As a consequence of Goal-Action Coupling, the learner begins to master the skill, which feeds forward to enhance her expectancy of being able to successfully perform the task.

As all elite athletes and advanced performing artists know, an intense focus on the goal, not the action, is what enables them to excel in their sport and art.

Let’s dive deeper into each of the 3 categories in the OPTIMAL theory framework.

Enhanced Expectancies

This is the expectation you have, as the learner or performer, of being able to execute the task successfully. Enhanced expectancy can be present both during the learning process, and further along after a higher skill level has been reached. Self-efficacy, which we saw in my earlier post [link], is one manifestation of enhanced expectancy, but other contributors such as socio-psychological factors also work in its favor. For example, perceiving a given task to be easy, rather than difficult; being told that one’s peers were successful in learning the task; even placebo effects and “lucky charms”, have been shown to increase a learner’s expectation about her own success. The theory posits a positive feedback loop where enhanced expectancy increases the number or quality of successful outcomes during learning, thereby increasing learning speed and retention, and further enhancing the learner’s expectancies.

Autonomy

Create a learning environment where the learner has control over the conditions of her learning process. As opposed to passively following conditions imposed by a teacher, coach or other third party, autonomy requires the learner to be proactive and intentional about how she wants to learn. The variant step of the APT discussed in my earlier post [link] supports autonomy by creating the latitude for the learner to make her own decisions about the variants of the phrase to practice, using a simple but precise guideline that is not overly imposing. Other autonomy-supportive methods include allowing the learner to control when and how she receives feedback: requesting feedback at attempts that she thinks are successful is much more impactful than receiving unsolicited feedback at arbitrary moments. For learners with less experience in devising effective learning conditions for herself, a teacher can play a guiding role in this respect.

Having autonomy over one’s learning environment can provide the learner a sense of agency and increase confidence around her learning capabilities. Autonomy combined with enhanced expectancy forms the motivational driver for learning.

Attentional focus & External focus of attention

Attention is the state of tuning out distractions and concentrating on only those focal points that are essential for completing the task at hand.

When a learner is performing a complex movement, to be concentrating on her physical self and consciously controlling her body movements is to be practicing an internal focus of attention. Most of us are familiar with internal focuses: turn my wrist a little bit this way! Curve my fingers more! Even if the movements may be perfectly correct from a technique perspective, the attempt to directly control one’s movement “freezes” the degrees of freedom of the motor system, and is impairs the learner’s ability to attain said technique with automatic movements and mastery. In contrast, external focuses shift the learner’s attention away from consciously constraining her movements, and towards tangible or intangible objects in her physical environment that are congruent to the task goal. We have seen intangible external focuses in the mirror example [link] and imagery methods [link, link] in my previous posts. Tangible external focus can include assistive equipment that are used to guide the learner’s movements; focusing on specific parts of the instrument, such as where on the key the finger lands; or even focusing on the music score. (More on these in future posts!) Provided that the external focuses are task-related, and not distracting, the learner’s movements are now free to occur naturally when her task is framed as achieving a desired outcome for the external object.

If you are a learner who relies on external focuses, you’re in good stead! It may seem counterintuitive to some, but external focuses are natural instincts; babies learn to walk not by focusing on their muscle actions, but by interacting with their environment. In fact, you may be relying on external focuses without even realizing it. Research studies have consistently shown that external focuses beat internal focuses in improving the efficiency and efficacy of one’s movement patterns. In a ski-simulator study, participants learned to perform slaloms better when they were instructed to focus externally on the wheels under the simulator platform, as compared to when they were instructed to focus internally on controlling their feet [Wulf, Höß & Prinz (1998)]. The curious fact is that a single word change in the instructions, from “feet” to “wheels”, was enough to boost performance!

Attentional focuses are relevant in both learning and performance settings. The astute learner will recognize that the attentional focuses that she practices when learning a skill (or music piece) are directly transferrable to the time when she has to perform the skill. Therefore, be deliberate about using external focuses when you learn a piece—they will come in handy at your next recital!

In a future post, we will continue with Part 2 of this series on the OPTIMAL theory, in which I will discuss additional related concepts and alternative research directions, and look at its implications for application to specific domains.

References

Wulf, G., Höß, M., & Prinz, W. (1998). Instructions for motor learning: Differential effects of internal versus external focus of attention. Journal of Motor Behavior, 30, 169–179.

Wulf, G., & Lewthwaite, R. (2016). Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: The OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. Doi: 10.3758/s13423-015-0999-9.

Leave a Reply