Since starting this blog, I had spent a good deal of time expanding my knowledge of the motor learning literature and music pedagogy, and pondering on my readings inspired me to experiment with new ideas that I’d discovered along the way. Today’s post is my learning diary. Taking a brand new piece, I journal the several days I spent with it, from the very first time I opened the score on my music stand, up until the masterclass in which I performed it.

My music choice is Debussy’s Prelude No. 2 from Book 1, Voiles. Knowing myself to already be fairly adept at learning technically challenging pieces, I was looking for something to grow my auditory imagination instead. I selected Voiles for its relative technical ease yet boundless scope for a complex auditory landscape. It’s atonal construction was also an musical challenge for my traditionally tonal brain!

If you wish to follow along with the score, IMSLP is a good resource.

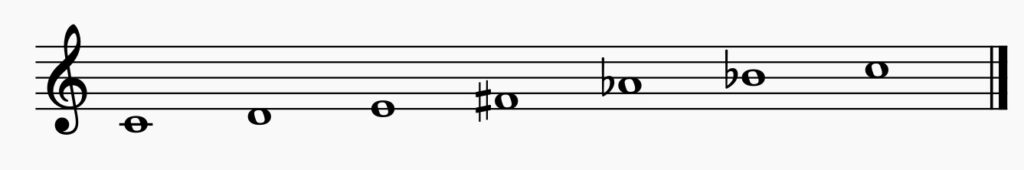

Day 1. Sight-reading through the piece was mind-boggling. Written in a whole tone scale meant that the traditional sense of tonality is abandoned. Only notes in whole steps are included:

My first instinct is to map the visual locations of the notes: the cluster of 3 black keys, plus the cluster of 3 white keys where the pair of black keys live. I just have to make sure to stick to those notes!

The accidentals in the piece were not friendly at all. Enharmonic notation sometimes follow one another! As I squint at the score to decipher what notes to play, I realized that part of the difficulty I was feeling was a disconnect between what I see on the written score and what I could usually expect from tonal harmony. Years of reading I-V-I progressions have made it a familiar auditory acquaintance and automatic motor skill. I was missing that aspect for this atonal piece. If only I could hear in my mind the atonal character of what I see on the written page, with the same clarity that I hear a familiar tonal chord progression, that would make my learning that much easier!

Day 2. At this juncture, I figured it would help my auditory development to listen to as many recordings as possible, and to get the overall sound of the piece in my head. As I listened to several pianists’ renditions on YouTube while following along with the score, I noted various contrasting interpretations: hazy or direct, no-frills or expressive, timeless suspension or an ebb, flow and flourish.

Debussy’s Preludes are beloved for their imaginative titles that are presented at the end of each piece, so that performers and listeners are encouraged to form their own idea of what the piece is meant to evoke before the title is revealed. In French, “voiles” has dual meaning: veil or sail. Which one do I want it to be?

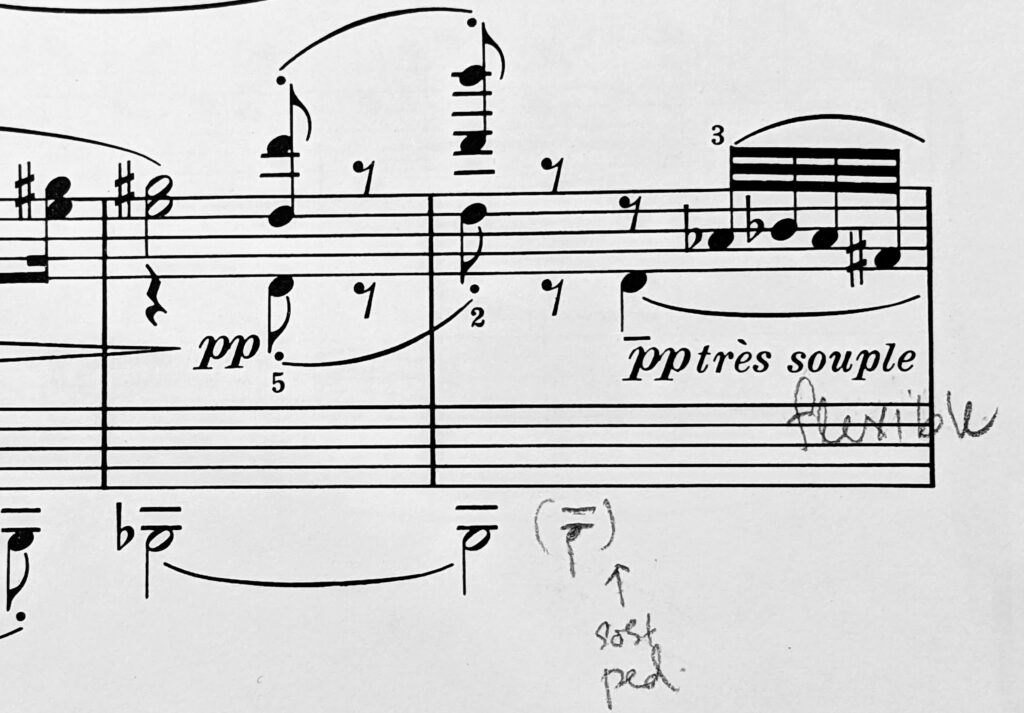

Day 3. I am back at the piano today. I begin with homing in on specific passages to sort out notation and performance choices. The second theme with a hypnotic ostinato pattern appears with the insistent B-flat in the bass. How do I pedal to not cut off the bass but still maintain the clarity of the ostinato and melody? I decide I would catch the bass with the sostenuto pedal, which would free up the damper pedal to align more closely with the other voices.

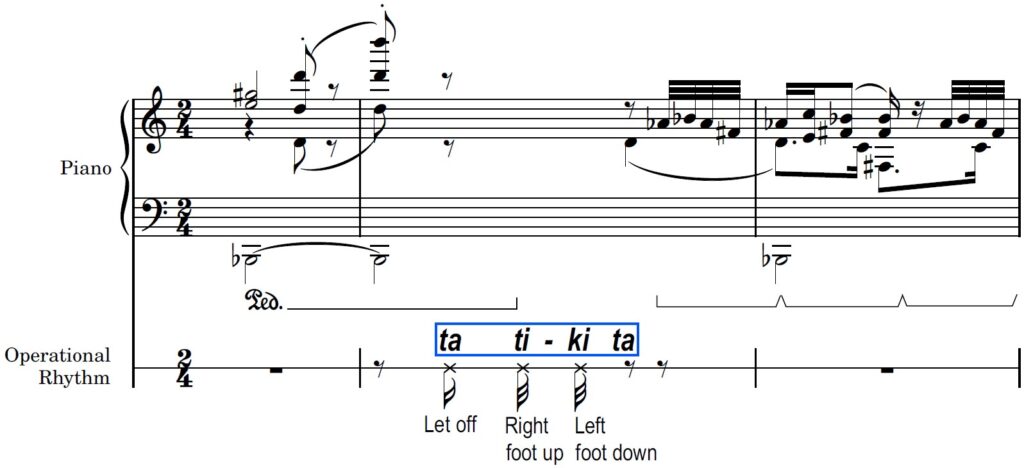

Getting the sostenuto pedal right turns out to be a tricky hand-foot coordination. The only logical spot to apply the sostenuto pedal requires me to silently re-depress the bass B-flat key, ease off the damper pedal so that the top notes come to a elegant close, quickly hit the sostenuto pedal right before the entry of the second theme with a fresh clean damper pedal. And, all of that has to happen without sounding like any of that happened. I step through this sequence of operations very mechanically, to check that the correct notes were captured at the correct step. At this point, I am feeling more like a piano operator than a piano player! Adding musical structure to the operations seems like it will integrate better into the music, so I assign each operation a precise rhythmic placement. Chanting in a “taa — ti-ki — taa” rhythm, I recite the mnemonic, “let off1 — right (foot up) – left (foot down) — theme”, whilst envisioning how the accompanying physical movements would produce the desired effect.

Day 4. Today is spent working through sections.

I try various expressions and imagery for the opening phrase. The descending motif sounds like mist drift gently down the mountain tops. Hold a second, Voiles means what, again? I settle on the image of a light fabric, itself having physical integrity, flapping irregularly in the wind with elegant waviness and mystique. I will try to keep a clean texture without being dry, and, in accordance with the Debussy’s opening instructions, “dans un rythme sans rigueur et caressant”, take liberty with the pulse in a not-so-predictable way to reflect the unpredictability of floating fabric.

The second theme returns an octave higher, shrouded in a C5-D5-D6-D5 ostinato pattern in the treble register. The sine waves rippling through my imaginary fabric engage my own body to move along. Actually, I had discovered by trial and error that rocking my body back and forth with the pattern made it easier to learn: without having to think too hard about the intermingling of the ostinato with the melody, I realized it freed up some mental capacity that I could direct towards voicing the melody.

Day 5. That pesky 1/32th note octave climax is just not sticking to my brain. I have already tried different fingerings, practiced rhythms and varied note groupings. Audiation-wise, the pentatonic scale of this passage is starting to sink into my ear, but the intervals still feel less than automatic, very hit-or-miss. What is my external focus here? Coming straight off from a 4-octave span glissando, I realize I never quite hit the start of the octaves the same way each time. That is the missing link. I quickly identify an approach: give myself a split second “reset” break to reposition my hands directly above the octaves. From here, strike in groups of 4 and let my ear take the octaves to the fortissimo climax. Reset-4’s-climax.

Day 6. I look down at my hands today. How different it is from looking at the score! I pick through the opening by ear (and with some assistance from photographic memory as well) but didn’t get far. More work to be done!

The rocking motions with the ostinato pattern are already feeling more natural today, as are the glissandos in the closing section, for which I had also figured to incorporate a matching lilt of my shoulders to synchronize with the moment I play the una corda pedal until when I release it. Timing it to catch only the small print glissando notes in a quiet haze, so as to not overpower the outer bass and melody lines, I savor the effect of the sonic contrast and atmosphere brought about by the selective touches of una corda and my little shoulder dance.

Overall I’m quite pleased with my choreography of the piece. It’s so fun to think of music making in the same way as choreographing a figure skating program!

Day 7. Work was crazy today. I have all of 25 minutes to practice, and the masterclass is tomorrow! What can be done in 25 minutes? I start off cold with a full run-through without the score. Although I am not intending to play from memory at the masterclass, I usually have built enough of a mental model of the piece just from working on it, to be able to play without the score. Testing the resilience of my mental model is part of my learning process, and it is also the foundation for more rigorous memorization work later on.

Disheveled is how I am feeling by the end of the run-through. Not surprising, as this was the first time I had played it from start to end. Nonetheless, this exercise revealed me the information I needed to know: my focuses seem to be mostly effective but not yet internalized; my photographic memory, always my strongest suit, tides me through the majority of the piece, but at points where even that failed me, my audiation faculty is just barely sufficient to get me stuttering through those passages by ear.

For the remaining 20+ minutes, I diligently review my focuses and rehearse for which passages I will look down at my hands and when I will glance at the score (including remembering where on the score to look! I sometimes lose my spatial orientation after looking away.)

Masterclass. Mr. Teacher is in storytelling mode. The Sirens are alluring, their enchanting song wafts through the ocean mist. The sailors set out to sea, seeking adventure with their tenor theme calling forth. They soon hear the Sirens, the theme rising in register amid the hypnotic ostinato. And there is no escaping their fate when their theme, by now in the high soprano range, finally gives way to the Siren song.

The beauty of Debussy is that there can be so many colorful and vivid interpretations of the music!

Footnotes

- Let off is the technical term for the depth of the key at which the hammer is still resting on the jack. Feeling for where the let off point is, and then gently depressing from the let off point to the key bed is the way to silently depress the key without sounding the note again. ↩︎

Leave a Reply