When I recently showed the Chopin Etude Op. 25 No. 2 to my teacher, he pointed out that my fingers were lifting too high—just that slightest bit up off the keys could hinder the ability to execute the piece at the required tempo. “I do really??” I exclaimed, to which he whipped out his phone and took a close-up video of my hands.

He was right, of course. But what struck me at that moment was, why hadn’t I thought of utilizing video feedback before? In figure skating today, video feedback is an integral part of every skater’s training regimen. Was my free leg bent? Were my shoulders level? Yet this was the first time it crossed my mind to use it for piano playing. Were my fingers lifting too high? Was my wrist motion efficient?

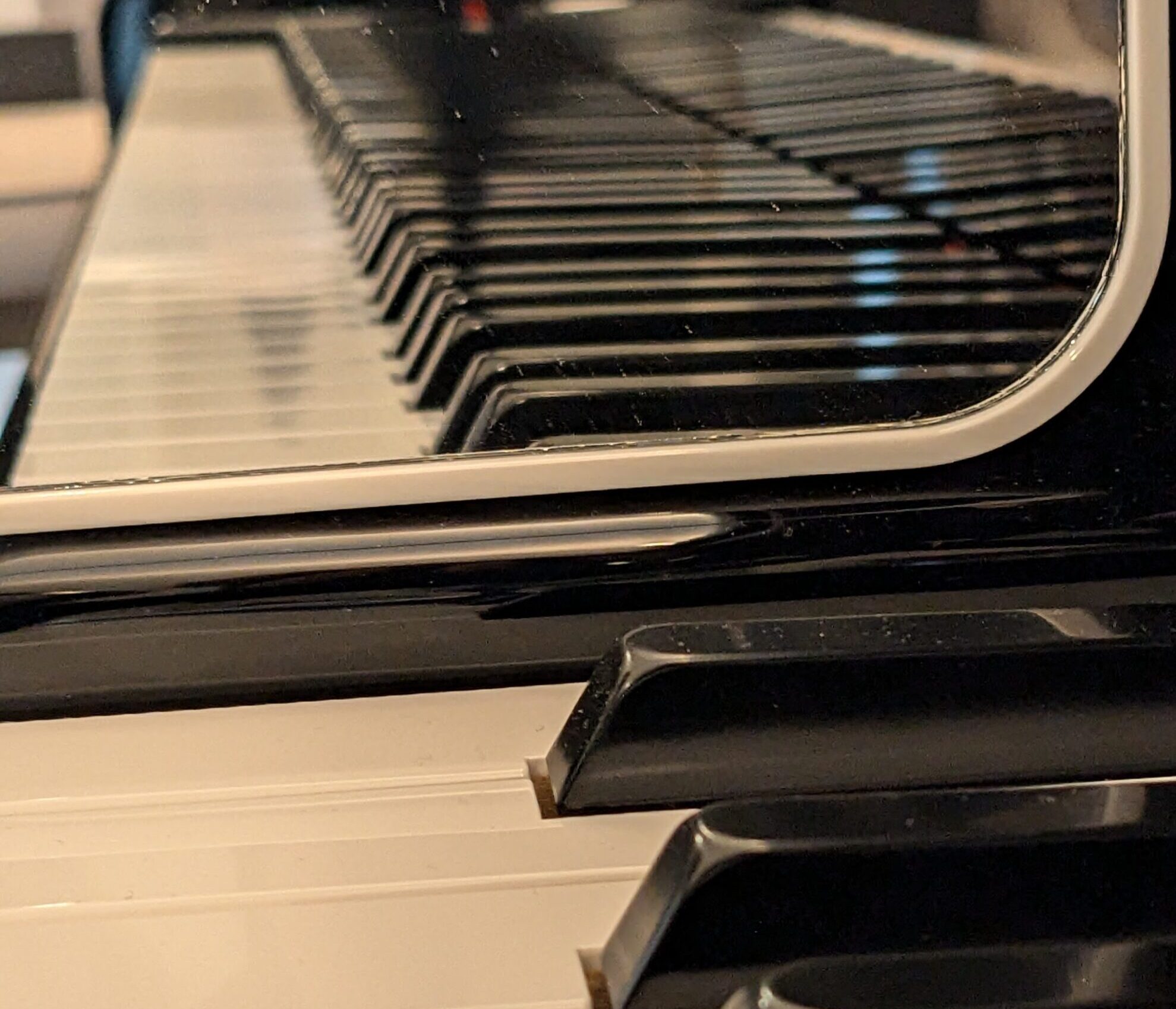

When I got home that day, I contemplated setting up a video recording rig. But then, I had a better idea. I went on Amazon and ordered a pair of mirrors for next day delivery, and set them up on either side of my piano.

Feedback is a crucial component of learning. When a learner receives feedback, she makes adjustments to her movements in an attempt to achieve the intended outcome. But not all feedback are born equal. We can all agree that feedback must be actionable and specific. But more importantly for motor skill learning,

Feedback must be immediate, ideally within seconds of the attempt.

There are neurological reasons that indicate the importance of immediate feedback for motor skill learning. Other performing arts already caught on to the secret of mirrors. Ballet dancers watch themselves in the mirror to attain the correct posture and aesthetic forms. Actors practice enunciating and emoting in front of the mirror. My skating club installed giant mirrors rink-side. The list goes on.

By watching my hands in the mirror while I play, the feedback I receive is as immediate as immediate can be, and I found myself making corrections immediately too. Now, my mirrors are my number 1 practice tool to ensure that I am achieving the ideal movement patterns.

Isn’t it distracting?

Not at all! In fact, mirrors double up as a task-related external focus of attention. It is an external focus because the pianist’s attention is directed externally towards objects in her environment (the mirror image) in order to produce an intended effect (correct movement of the hand’s reflection), and it is task-related because it directly relates to the goal of executing the correct movements. Research has shown that movement patterns learnt implicitly this way are more efficient and automatic than those learnt through explicit instructions. By trying to make the mirror image move correctly, the learner subconsciously organizes her own movements in the optimal way to achieve the desired outcome.

Isn’t it hard to watch a mirror while playing?

It is admittedly little awkward to crane my neck to look at the mirror. But, when used strategically, the benefits are immense. Use the mirror to work on short snippets, a measure or two, hands separately or together as needed, and only for the specific purpose of gathering immediate feedback. Then, after making corrections with the mirror, follow up with practicing without the mirror to solidify and retain the corrections. A bit of spatial awareness of the keyboard helps for not looking at the keys, but if you didn’t have the spatial awareness to begin with, you would certainly have it after!

What feedback mechanisms do you employ while practicing? Do you use mirrors or video feedback as well? I would love to hear your creative ideas for incorporating feedback—be it visual, aural, or other sensory modalities—into your daily practice.

Leave a Reply